The Only Light We've Got: Soul of a Nation in Bentonville, Arkansas

April 13, 2018

by Lisa Williamson

This past July at Colby College, visiting faculty member Dr. David Driskell discussed with IDSVA students the challenges curators face when researching works for shows such as the Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power. During its conception, the first question formulated was the same question Driskell himself contemplated as a young art student finding his voice: “What is Black art?” The question floats and lingers as I visit the Soul of a Nation at Crystal Bridges in Bentonville, Arkansas. Driskell says it challenges the artist to rise above the history of the separation of the races as ethos, as well as their individually self-imposed ethos. He reminds us, “Art is the only universal we have.”

Romare Bearden’s response that “Black art is the art that Black artists do,” situates the verb “do” as a founding principle of the Black aesthetic. The act of “doing” includes a search for form and meaning, a freedom from oppression. It reveals a paradoxical split within a visual social commentary between figurative/abstraction, violence/non-violence, literal/metaphorical. The courage to “do” is paramount to telling the tale, because, as James Baldwin says, “[t]here isn’t any other tale to tell, it's the only light we've got in all this darkness.

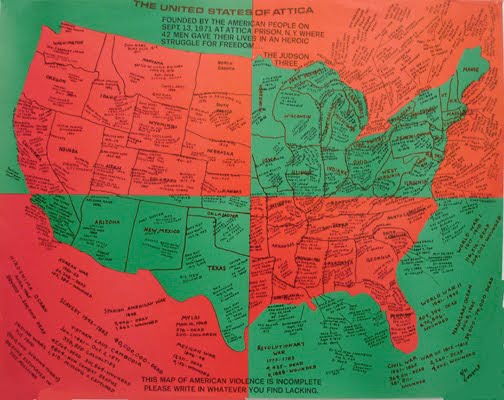

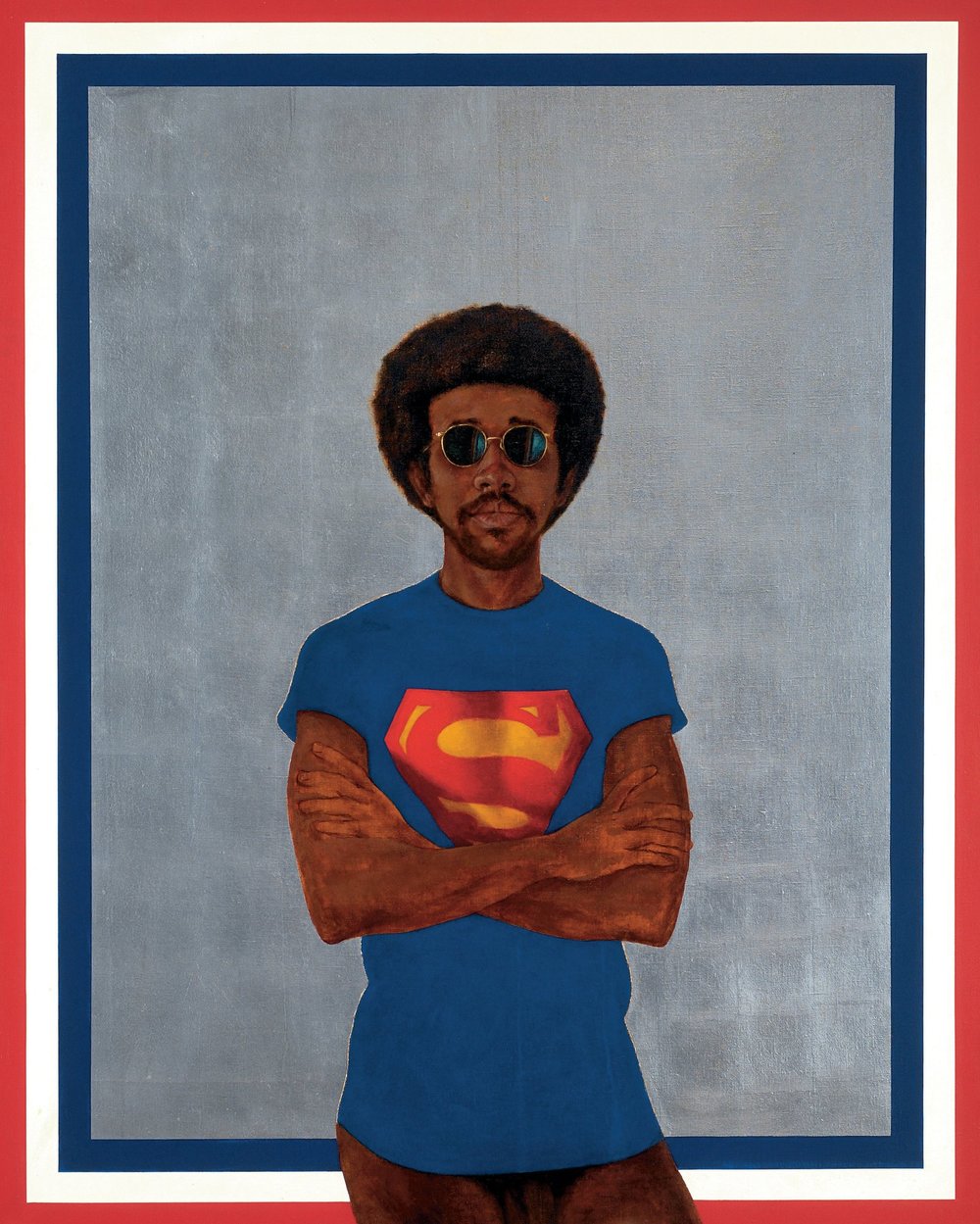

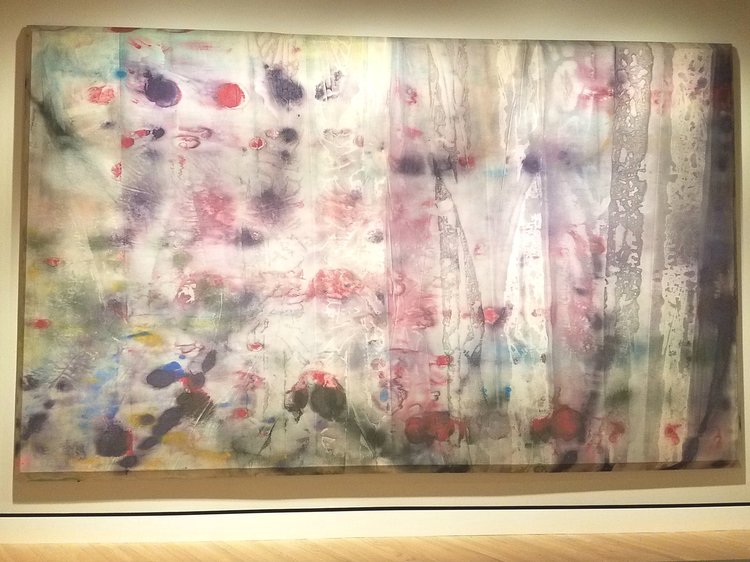

Soul of a Nation is a collection of tales. Barkley L. Hendricks’s Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved Any Black People-Bobby Seale) critiques the tale of a mythical figure while simultaneously inserting himself as his own hero. Sam Gilliam’s April 4 is a tale of collective sadness captured on raw canvas that absorbs purple, black and red teardrops shed for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Noah Purifoy’s Totem is an assemblage of rusty casters, discarded shoe forms, and smoked pipes, that tells the tale of the LA Watts Rebellion. Faith Ringgold’s United States of Attica tells the widespread tales of racial violence as a rebuttal to the false tales of “isolated incidents.” Elizabeth Catlett’s Black Unity is a mahogany fist raised in solidarity with Olympic medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos that reaffirms the tales of being silenced.

The micro-narratives move toward a whole picture of the rise of the Black Power Movement through art, but it is not a complete story. Many more voices have gone unheard, and their tales continue to be recovered. Credited as one of the “forbear contributors,” Driskell’s groundbreaking 1976 curatorial endeavor Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950 at LACMA, serves as the blueprint for Soul of a Nation. The relevance of the current show traveling from the Tate Modern in London to Bentonville, Arkansas cannot be ignored. The gravity of the show settles in my soul as I follow a winding path exiting the wooded museum grounds after dark, past a Confederate statue, to reach my car. In a region recognized for its history of racial violence, it dawns on me that the tales that challenge the grand narrative continue to be the only lights we really have.