Joy and Fear by the Theatrum Orbis: Contrasting takes on a Biennale Theme

November 22, 2017

by Angela Whitlock

The Venice Biennale’s theme was humanism, specifically the kind of humanism that deals with the celebration of mankind’s ability, by way of art, to avoid being dominated by powers that govern world affairs. The artistic act can be viewed as an act of liberation, resistance, and generosity. Art can bear witness to a precious part of individuals that make them human, especially during a time when this humanism is jeopardized. Art is the ultimate ground for individual expression, freedom, reflection, and significant questions. In today’s world, the role, voice, and responsibility of the artist are exceptionally crucial, considering the framework of contemporary debates.

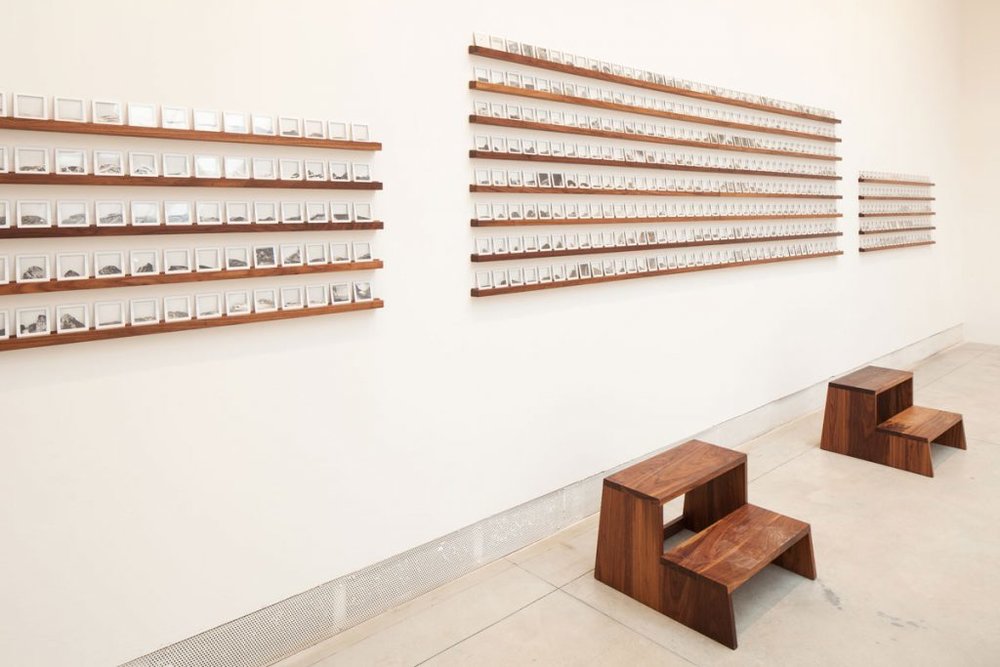

One of the artists who exemplified these issues was Hajra Waheed, whose section within The Pavilion of Joys and Fears consisted of small-scale, rectangular paintings displayed on wooden shelves on two parallel walls and a copious amount of small glass slides on the adjoining wall. Waheed uses complex narrative structures to explore issues surrounding covert power, cultural distortion, mass surveillance, and the traumas and alienation of displaced subjects via mass migration. Specifically, the slides were small cut outs of of sections of images mounted onto glass that could be viewed under a magnifying device. Both the slides and the paintings were a reflection of a time where photographs were not permissible within her country. She created the images as a way to liberate herself from these confines and to resist these boundaries. The paintings contained images of smoke and water, while others were almost completely dark blue. Staggered in between these paintings were hand renderings in different positions: hands holding flowers, hands cupped, and hands open. To me, the images evoked ideas about the four elements of nature (earth, air, fire, and water), while the hands symbolized generosity. For example, I took the hands holding flowers to mean the giving of a symbol of peace. On the parallel wall, one of the paintings consisted of a woman whose back was turned, suggesting an act of resistance or defiance.

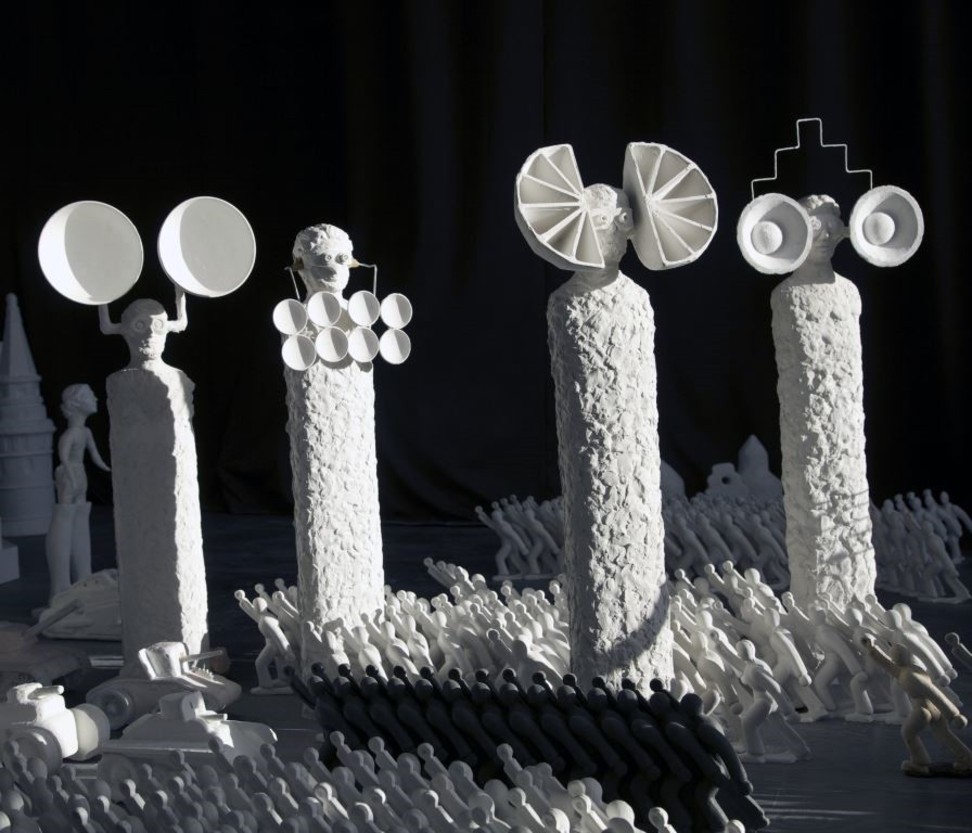

The Russian pavilion also prominently displayed the theme of humanism as an act of resistance and liberation by showcasing three artist’s interpretation of liberation from oppression, an act of resistance in itself. The artists Grisha Bruskin, Sasha Pirogova, George Kuznetsov, and Andrey Blokhin created what is called “Theatrum Orbis,” borrowed from Abraham Ortelius creation of a world that is compiled of comments of travelers and missionaries. The top room consists of white sculptures on pedestals that contain powerful language, such as “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,” “Dialectic of Enlightenment,” “Death of the Author,” “Beyond Good and Evil,” “The Will to Power,” “Nothingness and Being,” “The Pleasure Principle,” and many more, which, for me, evoked themes and titles belonging to philosophers such as Heidegger, Derrida, Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud. Some sculptures symbolized feminine and masculine, while others were technological in character but not in functionality. In a separate room, there was an arrangement of figurines that were part human/animal and part machine. It appeared that technology was encroaching upon the human form, which was reminiscent of themes discussed in Franco Berardi’s lecture in Spannocchia. The herd was present again in this room, with a collection of men marching in a cluster, indicating powerful messages regarding the effects of mob mentality, as one group encircled what appeared to be an idol being worshipped. Army men were also scattered throughout this display, allowing viewers to make a connection between technology and politics or warfare.

The video that played on a loop took over the entire perimeter of the top room, leaving the white sculptures in the darkness. The video began with men marching, indicating a herd mentality, and ended with the idea of liberation through resistance by way of a magical dance of people and elf-like creatures emitting light and the idea of freedom. The bottom floor of the Russian pavilion consisted of human segments encapsulated in jagged formations, with only portions of the human forms sticking out. These were intended to be influenced by Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” and the journey around the ninth circle of hell where the most awful of criminals suffer. These figures are frozen in ice, doomed to spend eternal damnation in a cold isolating existence.

The idea of the Baroque was prominent in each of these artist’s works, in the sense that both produced elements of drama and tension, although I believe that the artists’ works within the Russian pavilion had more of an exaggerated element of grandeur than Waheed’s pieces. This was primarily due to the multimedia aspect within the Russian pavilion which created an overwhelming sensory experience, along with the stark contrast of all white sculptures against black backgrounds. Waheed’s imagery, however, appeared rather haunting and dreamlike as opposed to being involved in sensory overload. Her imagery was also more subtle when it came to reading into the theme of the Biennale.