Hope for Better Days: Art and its Reflection Upon a Fractured Condition

November 16, 2017

By Nicole Marie Milchak

In a world full of conflicts and jolts, in which humanism is being seriously jeopardized, art is the most precious part of the human being.

– Christine Macel, Enclavia: Painting, a Consequence of This Kind of Life, the Pavilion of the Republic of Serbia, Giardini, 2017.

The 2017 Venice Biennale identifies itself as the collective majority Other, perhaps for the first time. The Biennale concerns itself with the state of humanity: the polluted ecosystem we call home; the technological framework and network which collects our ideas and archives our days; the inhumanity of a top-heavy power structure pervading more nations than not; and finally a nod toward a romanticized version of past epochs replete with Baroque-era tension, richness, and drama.

%252C%252B2017.jpeg)

Venice "La Serenissima" Pavilion (detail), 2017 Photo Credit: Nicole Marie Milchak

The hearkening back to the Baroque era in its truest sense is most prevalent in the Venice Pavilion of the Biennale, where one can witness a montage of cinematic moments from Hollywood’s classic, goldn, and contemporary eras which take place in the land of La Serenissima; and sample the handiworks, customs and costumes, exuberance and indulgence indicative of days past. Most noteworthy is the juxtaposition of the indulgence of the Baroque era: the extravagant wig-making and the finest of shoemaking, speaking to La Serenissima’s rich heritage of international trade, voyeurism mixed with exhibitionism scandalized and/or covered up under mixed masquerade and charade; compared against the work of neighboring pavilions within the Giardina, the Arsenale, and scattered throughout the city of Venice. While the Venice Pavilion stands as a rich hearkening back to yesteryear, other pavilions took another side of humanism, another side of the sign of our times, of simulacra and connection coming from the same source, as part of the international discourse that is the 2017 Venice Biennale.

The Czechoslovakia Pavilion, Swan Song Now, by Jana Zelibska, is an installation resting upon the juxtaposition of girlhood and womanhood; of kitsch and high art, the relativity of time and space; as well as spectatorship and voyeurism, all through the metaphor of the sea (a recurring theme in the 2017 Biennale): a place of genesis, forgiveness, and the familiar; as well as a backdrop of the darker sides of human desire and consciousness, alienation, pollution, and yet rebirth to such metaphorical degrees as the expansion of (both real and imagined) hemispheres, convergence, and dimensions. In this installation Zelibska brings large readymade lights shaped like swans, intentionally and fixedly positioned in both space and time, to the forefront of the voyeur’s field of vision. A large video projection encapsulating the sea and which takes up the entire view beyond the field of readymade swan lights, a simulacra of the real sea, is situated on the wall behind the ground field of sculptures. An infinity of dreamy, incoherent sound emanates from the video simulacra of the sea and the room at large. One is transported to their own inner consciousness and that of the collective consciousness of memory and regret until the eye rests readily upon two videographic portraits of adolescent girls which change ever so slightly in a gaze of the object’s eye: from a state of ennui to irony, from self-actualization to confusion, much like the state of adolescence and the questioning of identity therein personified.

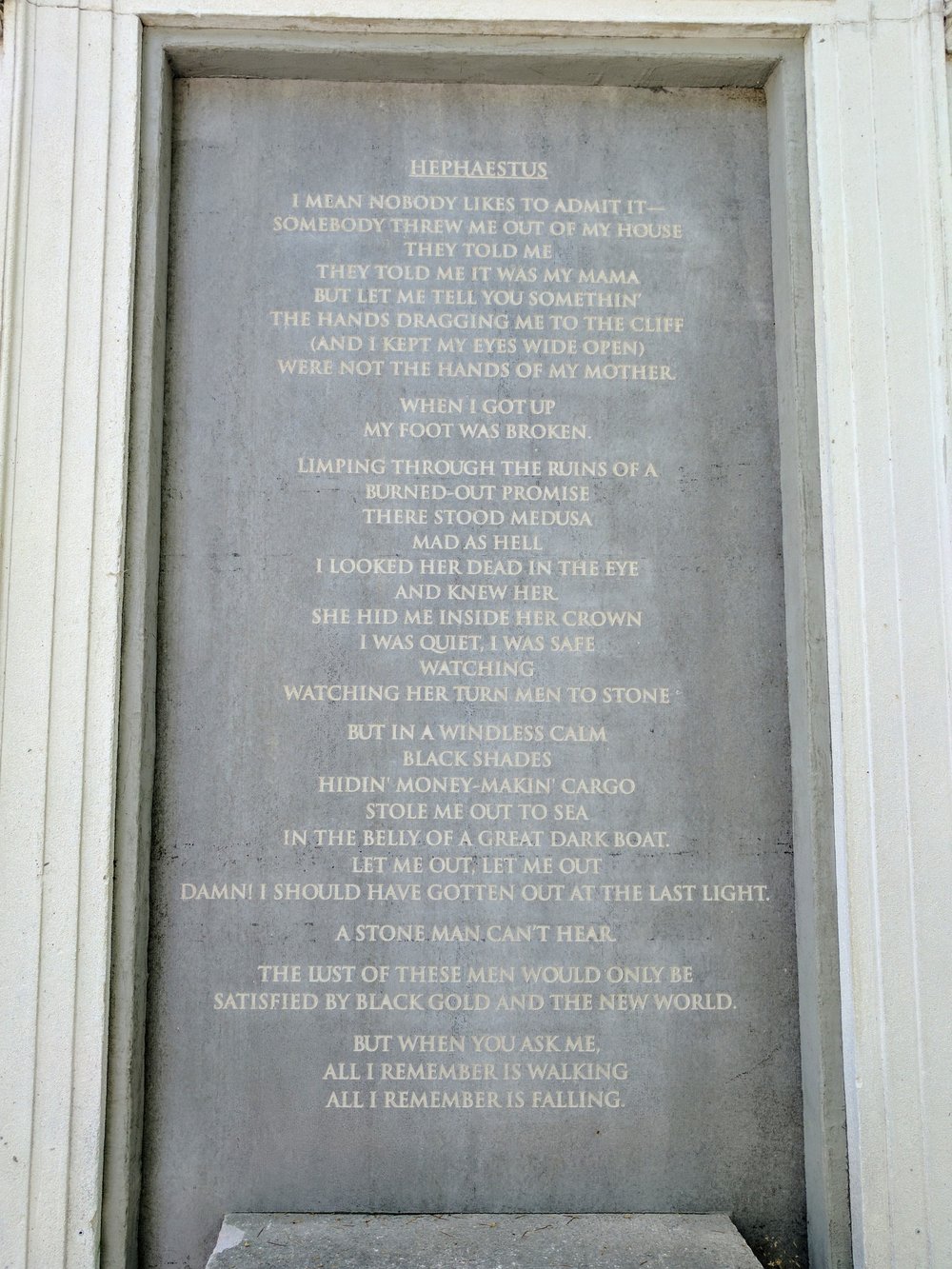

The abundance in the Venice Pavilion compared with the dreamscape of the Czechoslovakia Pavilion against the America or Russia, or even Canada Pavilion (where water is brought up yet again, this time as a jettisoned fountain “spouting from Walden’s Pond” according to the side description of the Canada Pavilion) is a sharp one: America and Russia are both soberly addressing the spirit of our times, that of dictatorship and mass (hyper)production and lack of realization and even representation to the point where personal mythologies and identities are unrealized or punctuated by the state. In the words of Mark Bradford’s Tomorrow is Another Day of 2017, from the side of the American Pavilion, and in conclusion:

HephaestusI

Mean Nobody Likes to Admit It-

Somebody Threw Me Out of My House

They Told me

They Told me it was My Mama

But Let Me Tell You Somethin’

The Hands Dragging Me to the Cliff

(And I Kept My Eyes Wide Open)

Where Not the Hands of My Mother…

The 2017 Venice Biennale is a testament to the fact the art shall live long, and art shall save us all: as a reflection of the times in which we live, a reminder of yesteryear, and a sign of light and hope to the future hopeful.