CAA 109th Conference - Virtual Panel Recap The Aestheticization of History and the Butterfly Effect

by Nancy Wellington Bookhart

Cohort ’11

The session, The Aestheticization of History and the Butterfly Effect, at the 2021 College Arts Association (CAA) opened with what resembled a poetic psalm by the American artist Kara Walker. Taken from Rebecca Peabody’s text, Consuming Stories: Kara Walker and the Imagining of American Race, Walker states:

At the lowest moment…like Pandora, I actually thought, ‘oh, hope is the one thing that I have to give.’ You know, if I can give anything to a public. But what can it be, what can give hope and still contain these ideas of civilization at its end, or of destruction? Ruins, ruins, ruins is what I kept coming to. But what about those ruins that we keep going to visit? They remind us about hope.

The session explored those ruins of history, those sealed and fragmented stories. We are hopeful that this format will lend credence to the sensibility of the thought expressed in the live session.

Bookhart: In what ways do we regard the artists' works as historiographic texts and what does thinking about artworks as historiographic texts afford us?

Christina Corfield, University of California Santa Cruz: I have considered my research-based practice as historiographic in its visualization of historical facts. Importantly, it does not simply reconstruct a story about the past. Not that any visualization of the past simply “tells” a story, of course, but my purposeful rejection of historical accuracy is different than a creative interpretation of events. The facts I visualize invite rather than simply tell, acknowledging that a historical record exists but then interrupting that record, creating space to rethink given histories and their authority, and ultimately inviting speculation about what other stories are to be uncovered, recognized, or additionally given space. The points at which alteration of the historical record takes place are opportunities for critical inquiry. They are, as Mahsa Farhadikia a fellow session contributor noted about the work of Iranian photographer Azadeh Akhlaghi, the “punctum” of the work. They serve as an activation point for imaginative and emotional engagement that aids viewers in pushing beyond the image, to meaning that lies outside the limits of that image (Barthes 45). In this place of alteration/pushing beyond/imagining, the text is no longer simply trying to tell a specific (hi)story. Like a portal or gateway, it solicits participation from the viewer, actively asking for subjective experience and personal knowledge, appealing for other stories, memories, thoughts, traditions, and processes of meaning-making, thus expanding the “official” discourse around the event or (hi)story depicted.

Bookhart: According to Jacques Ranciere’s concepts of the distribution of the sensible and the regimes of art, the boundaries of making and doing, art and philosophy are blurred in the aesthetic regime which allows the work of art to be read in historical terms as a restaging of history. How then do the processes of aestheticization (gathering historical information and then translating/adapting/arranging/altering) create opportunities for imaginative immersion, historical engagement, or political activation of/for viewers?

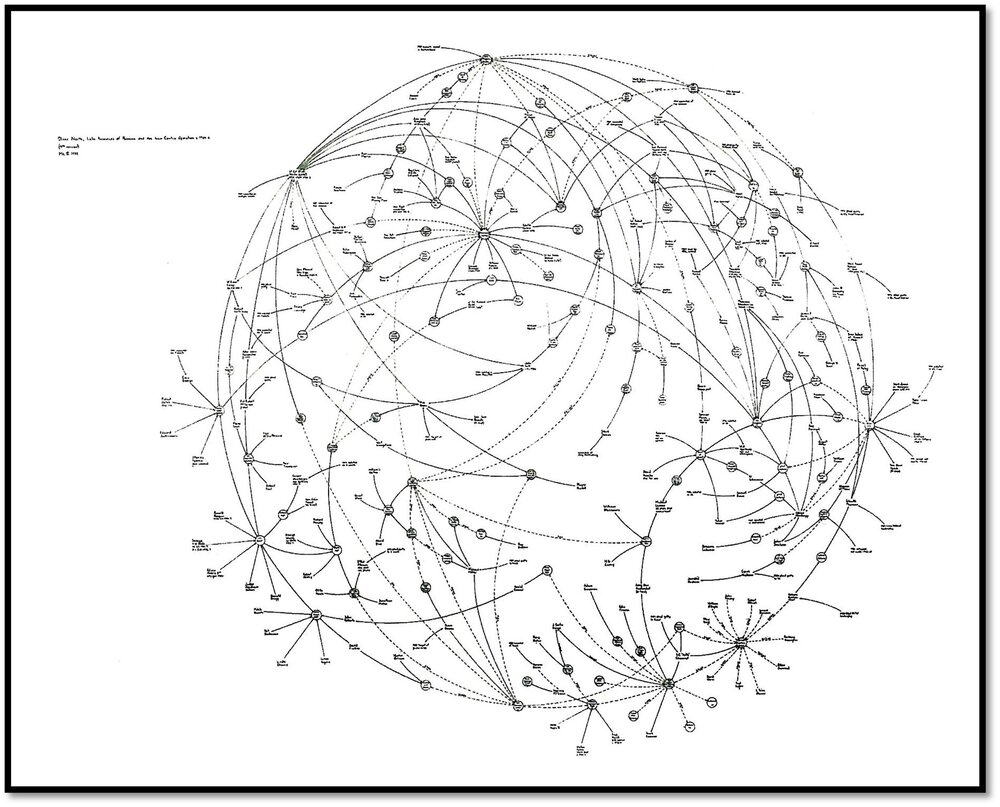

Paige Lunde, IDSVA, Ph.D. Candidate, Cohort ‘13: First, we must consider how the techniques that have established history have also imposed reification. When Franco Berardi writes about sensibility and aesthesia in The Uprising, he directly relates them to “the technological transformation of communication and work” (Berardi 143-44). Berardi understood that technological alterations have compromised sensibility. My research, then, promotes the artist’s method of labor to resist those normalizing techniques that aim to lock down a particular history. Mark Lombardi’s artistic practice is an example of the artist’s gesture as a different kind of participation. His diagrams materialize thought processes that “mediate the hinge between aesthetics and information at the fundamental level of drawing (Law 7). The artist’s practice entails techniques that recapture/alter/ mediate historical memories embedded in expressions for their unconsidered potential. Building off of Christina’s point, making alterations to the historical record offers moments of critical inquiry that provides us with a path to challenge the authority that claims ownership over knowledge. Those moments of involuntary memory, for Walter Benjamin, prompt the imagination. Involuntary memories perform like a “punctum” and escape normalizing regulations. In those moments, we begin to recover a relationship with those expressions embedded in memory and, as a result, experience the “imaginative immersion” of a historical dialogue.

Bookhart: The question of the ownership of knowledge is the very impetus of the question concerning history that necessitates a re-evaluation of concretized history. How are ruins, potential, and hope activated in your research project in what Walter Benjamin calls the “dialectic turnabout” of history as aesthetically emancipatory (Buck-Morss 338)?

Mahsa Farhadikia, Independent Curator: I would like to start with the notion of ruin in the staged photographs of Iranian photographer Azadeh Akhlaghi. “By an Eye Witness” is a series of staged photographs by Azadeh Akhlaghi in which she recreates seventeen significant deaths in the history of Iran that happened between the constitutional revolution of 1905 and Islamic revolution of 1975. The series is based on the events from which no historical evidence exists due to the lack of technology and governmental restriction. In this sense, these photos are the conceptual blocks built on a kind of ruined or, in other words, absent history. This lack of historical evidence, on the other hand, gives those incidents a good potential for being interpreted from various angles. Here is where hope enters the stage. By the simple act of addressing the assassination of freedom fighters in Iran’s history—which in and of itself is a big step towards opening conversation about human rights issue—Azadeh Akhlaghi gives voice to those who were voiceless or to those whose voice was silenced. By making visible the images which were supposed to remain invisible, she makes us hopeful about a similar possibility in the present time. Thus, by bringing the political murders of the past to the fore, she evokes similar incidents in the present and creates a discursive space for discussing issues like dictatorship, censorship, freedom of speech, and suppression of intellectuals.

Bookhart: In the final analysis, if history was taken at face value as the sedimentation of all things, unchangeable, untouched by the revision of thought, then everything in human existence would reflect a type of timeless determinism. The aestheticization of history’s answerability resides in Friedrich Schiller's On the Aesthetic Education of Man, in which Schiller states, "we must be at liberty to restore by means of a higher art this wholeness in our nature that art has destroyed” (Schiller 45).

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

Berardi, Franco. Uprising: On Poetry and Finance. Delhi, India: AAKAR Books, 2017.

Buck-Morss, Susan. The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. MIT Press, 1991.

Law, Jessica. “Drawing a Line: Towards a History of Diagrams.” Drain Magazine, Vol. 15:1, 2018. http://drainmag.com/drawing-a-line-towards-a-history-of-diagrams/

Schiller, Friedrich. On the Aesthetic Education of Man. Translated by Reginald Snell. Dover Books on Western Philosophy. Dover Publications, 2004.

0 Likes

Share