A Studio Visit with Iñaki Bonillas

April 24, 2020

by Xenía Hodza, Cohort ’19

When moving my mother from her house of forty years, she proudly and bravely gave me her collection of random household family photos and half-baked albums. Thanking her grimly for the musty, moldy, 40-pound corrugated box in which she put them for transport, I was slightly repulsed and dimly aware that they would now either sit in my own attic for an additional forty years, or simply have to be tossed.

Iñaki Bonillas, an artist-philosopher, if there ever was one, would do no such thing. From his grandfather, Mr. Bonillas inherited a veritable archive of 4,000 amateur Ektachrome photographs which have been material, and muse for him during the past fifteen or so years. On a visit to Iñaki’s studio, we were drawn into and seduced by the extraordinary parallactic of the archives’ double life and the unassuming, sincere man who was using them as medium.

Led by two of our professors, the handful of us buzzed through the gate and escorted up the stairs by two lively dogs into Iñaki’s flat in the Roma Sur section of Mexico City. It was dusk outside already, but we were able to admire the thriving garden on the terrace, making it back inside in time for the warm glow of lamplight to start suggesting we were part of something special, something intimate, those moments that only happen in the hands of a generous spirit.

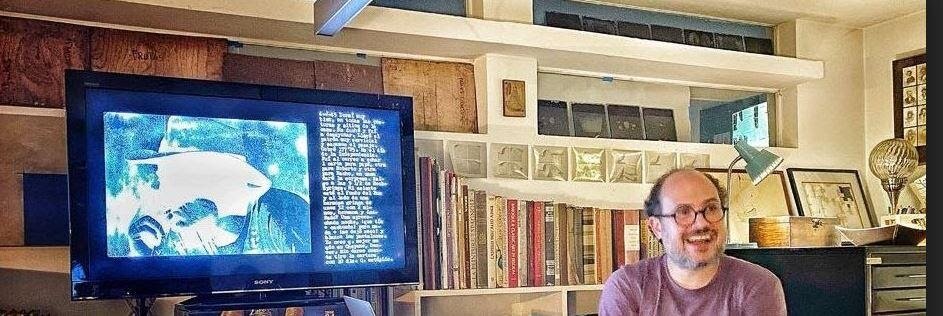

We were offered seats on a sofa and chairs directed toward a screen propped up high on top of the only item that seemed out of place, a cardboard box advertising Modelo Mexican beer. Iñaki began his presentation by apologizing for things that needed no apology, like the makeshift monitor stand, and offered us a large tray of Ferrero Rocher Italian chocolates.

Sitting at his worktable in a plum-colored tee shirt, Iñaki began showing us images of his work. He explained that his grandfather, J. R. Plaza, who had been a salesman, also enjoyed taking photographs. He took them in Spain and continued to do so when he arrived in Mexico City. An obsessively organized man, Señor Plaza compiled thirty identical leather books, each containing exactly the same number of pages with one photo per page, in approximate chronological order. Before gluing them down onto the thick, rough, black pages, he often wrote some kind of mark — an annotation, or a description of the subject or the location in which the photo was taken. Some of the abbreviated bits of text, that Iñaki said, felt even poetic. In fact, one of Iñaki’s dramatic exhibits consisted in photographing the backs of the photos, which held onto a dot of black paper where the glue was, punctuating a word or two written by his grandfather.

Nothing is lost on this artist. He is keen in reflecting upon the most obvious and, therefore, little attended-to appearances. The hand in the work is for Iñaki one of great importance. Even though he often now works with digital images, he is well aware that “something is lost.” Some of the archive has now been digitized and he senses an abyss between looking for an image among the 60-odd, double-sided pages of thirty books, and searching on his computer. The computer, which delivers all of the images at once in an identical format, takes no time at all. But the books, the archive — with each caress of the pages, a ritual begins, a much more deliberative conversation with the past, with his grandfather, and with everyone and every place, speaking through the tactility and visibility of the pasted prints. So, too, the motions of his hands, perhaps elbows, and certainly fingers, and eyes, and head, turning the pages and looking from right to left, are all so different from the motionless acts of sitting, in front of a screen, clicking on a mouse.

Every time Iñaki thinks he is done with the photographic archive, that he has exhausted its wealth, its usefulness and inspiration, he finds that it has become almost defiant. It speaks to him ever again, as if it will not release him. Every time he tries to do a project without it, he finds it calling him back. Back to an image, to a person, to a room, or a word. Perhaps it contains everything. Everything an artist ever really needs: Iñaki’s devotion to contemplation, practice, and reverence for seemingly innocuous materials, and yet, to the life work of another.

©Xenia Hodza, 2020. All rights reserved.